The Bundelkhand Express #11107 arrives in Allahabad from Jhansi, India.

The train is late. We wait. It will transport us overnight to Allahabad (ALD) and into Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state and one with the largest number of people living below the poverty line. My son and I have been in India for six days. We have yet to see anyone on top of a rail car. We don’t see unaccompanied children. The station in Jhansi is filled with young men, just as we have seen in the streets and shops. When I asked an English speaker about the lack of women out and about I was told, “Many women remain in the home with their families.”

It’s nearing midnight. The station has a waiting room for women only. A few elderly ladies dressed in colorful saris and some mothers with young children sit on the benches wearing forlorn faces. I don’t know if men and women travel in different compartments on this train. In Delhi, the metro trains had a women’s car. I chose to ride in one and found it comfortable – less crowded, less noisy and less smelly than the other cars. Will it matter to the men if I am sleeping in the same space as them? Will it matter to me?

The sleeper car aisle on the train to Allahabad. No doors separate one unit from the others.

When the train arrives we board and look for our beds. I don’t know what to call the sleeper spaces on this train. In size, each unit is comparable to a bedroom closet in the U.S. It contains six pulled down beds in two rows of three with a window between the rows. On the other side of the aisle are two more beds that also hang from the wall by cables. One unit in from the train car door, my son Henry spots his place on a top bunk. He climbs a small ladder at the bed’s head and settles in. My bunk is in the middle, beneath his.

Men occupy all the beds in our unit. I try to reach the middle bunk by climbing the ladder Henry uses. But, I cannot swing my body around to reach the middle mattress. He’s tired and I am stranded on this tiny island between the rows of beds. I whisper to Henry, “I can’t get into the bunk.” He sounds irritated and murmurs, “There.”

A young man in the middle bunk across from mine props himself up. He points to the bottom mattress. I hear Henry say, “Step on it.” I do so, straddling my legs on the two bottom bunks. One of the men is awake. He’s wearing a turban and a long white nightshirt. I reach up and heave my body atop the middle bed. “Shukriya” I say (thank you in Hindi). The young man smiles and gives a little laugh. His brown eyes settle elsewhere.

The gender issue I’ve conjured up in my head vanishes. I want to talk with him. “Where are you going?” “What will you do there?” “Where are you coming from?” “What’s it like…” My questions linger unasked and unanswered. My phrases in Hindi are limited.

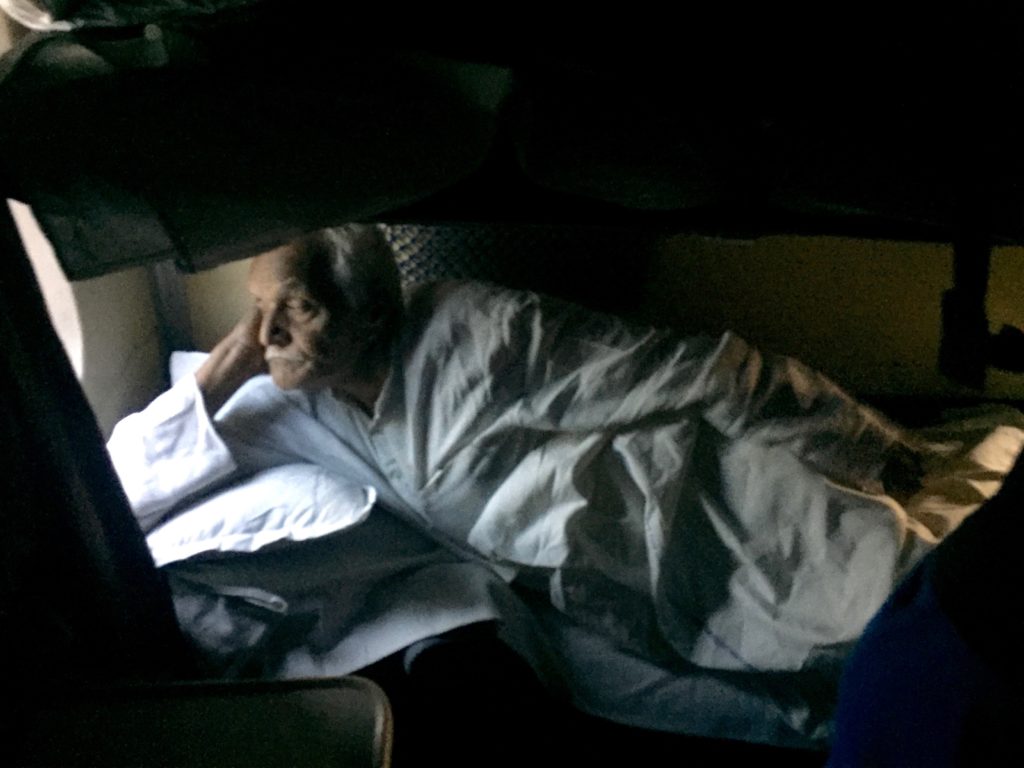

Time to contemplate from the bottom bunk on the train to Allahabad.

I don’t check to see if the sheets are clean or go to the bathroom to wash my face and brush my teeth. I drop my glasses into the black net that hangs from the wall. My space for the night is comfortable. I rest my head on the small pillow and listen to the train make its way through a black landscape. I let the this lullaby surround and settle me.

The overnight train brings us to morning. At the train car’s open door I get my first glimpse of the Ganges River (referred to locally as Ganga). Its dimpled surface reflects the sun’s light. People on the train raised their forearms to their chests and clasped their hands at the sight of the river, my son told me later.

We look shabby. I push the bed up and collect my things. In a matter of minutes the men in my unit become presentable. Shoes on, hair combed, shirts tucked, enough to go to work or meet their families. The train stops. They pour into the crowd of men at the station, streets and shops.