“It is better to travel well than to arrive” – Buddha

“It is better to travel well than to arrive” – Buddha

The shop stalls in Negombo were packed with beads, Batik dresses and bright blue elephant pants that added a burst of color to the streets. “You’re friend just bought a skirt,” called out one of the shopkeepers in English. I laughed at his assumption that all ivory skinned people on the street must be friends. At the same time I knew my own assumptions would be challenged while traveling in Sri Lanka, especially because I was traveling with a new friend, Bhante Sujatha, a Theravada Buddhist monk and native of this country.

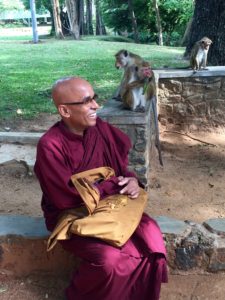

Known by many as the “loving kindness” monk, Bhante’s physical stature is small, more like that of an adolescent boy. His smile is boyish too, at times impish. I met him at the Blue Lotus Temple in Woodstock, Illinois, where he is the abbot and founder. Ordained in Sri Lanka at the age of eleven, he has been living in the United States for 20 years. For the past six years he has taken a small group of Americans to visit his native country. I readily accepted his invitation to join them.

Bhante Sujatha at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Peradeniya

In the western coastal city of Negombo, about 20 miles north of Colombo’s Bandaranayake International Airport, my ears echoed with the sound of ocean waves, vehicle beeps, chanting, bird calls, and drumbeats. What I was looking for on the street was a fan, anything to stir the sweltering July air that hung like a cloak. While the ocean waves churned at Negombo’s shore, no one was swimming. To do so would be like jumping into a washing machine.

Sri Lanka is an island country equivalent in size to West Virginia with a population of 22 million people. Buddhism is the country’s official religion and Sinhala is its official language. Surrounded by the Indian Ocean, this small nation is positioning itself as a player in global maritime trade. The country appears poised for progress and tourism.

Whether on a hotel rooftop or beside a lake, in the jungle, on a mountain, under the clouds, or at a savannah, seven people sitting still did not raise questions. Of our daily mediation Bhante said, “It’s okay to have thoughts. Just don’t tell yourself stories.” I learned to quiet my storyteller mind. Following each meditation Bhante would lead a short Dhamma talk related to Buddhism’s Noble Eightfold Path. I quickly realized that of those on the trip I was the least knowledgeable in Buddhism. Bhante was open to questions but rarely offered answers. An approach I came to respect.

From the Pinnawala Orphanage elephants walk through town to the river.

Driving from Negombo to Kandy we stopped at the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage. Sri Lanka boasts the largest gathering of wild Asian elephants. The Orphanage is home to its largest tamed herd. No fences separated the elephants from us, though handlers stood nearby. The elephants trumpeted and grumbled a deep guttural sound. I recorded the sound with my I-phone. It was unexpected, sounding more like a tiger than an elephant. Like so much of what I heard, I didn’t understand the sound’s meaning. When I looked into the eye of an elephant I felt humbled. When I stroked his dry, rippled skin he became real, not a photo, nor the subject of a TV documentary or a little girl’s dream.

Twice a day the elephants walk through the streets of the town to the Maha Oya. From a restaurant balcony we watched the elephants bathe and roam in the wide river’s shallow water.

Elephants bathing in the Maha Oya in Sri Lanka

As we walked people paused to bow in front of Bhante. He told us, “They are not bowing to me. They are bowing to the robe I wear.” His ruby colored robe symbolizes Buddha spirituality, Dhamma (truth) and Sangha (community). He explained that the bow was an act of surrendering, of lessening one’s ego. “No robe, no monk,” he said.

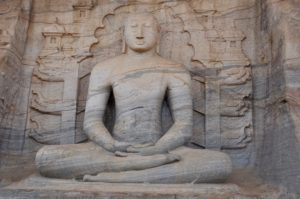

Our driver, Ari, navigated the city streets and dirt roads past the coconut plantations to Kandy, a UNESCO world heritage city. It’s easy to think of Sir Lanka as a Buddhist country. Buddha statues are prominent in many public spaces. They appeared on public streets, at railroad stations, in caves and stupas (mound like structures) and temples. “The statues are everywhere because that is how people think inside,” said Bhante. “We try to put what we think inside, outside. Like how writing thoughts becomes a song. These statues are chiseled by hand.” Seventy percent of people in Sri Lanka identify as Theravada Buddhists, but there are pockets of diversity. Statues of Jesus or sculptures of Shiva and Ganesh were rare, but present. Hajibs and kufis covered the heads of people in a Muslim neighborhood in Kandy. A variety of languages and music along with a whiff of the street food revealed these faith traditions – Buddhism, Hindu, Christianity, and Islam.

Sunatha Suwaya meditation and retreat center in Kandy.

Our jeep chugged up a steep, dirt mountain road to arrive at the newly opened Sanatha Suwaya, a modern meditation and retreat center built through Bhante’s non-profit global initiative, the Sanatha Suwaya Foundation. Its outreach program offers mind/body wellness classes and performs charitable works for local and international communities. The Center’s layered floors jutted from a tree-filled mountainside. The smooth cement floors and glass walls connect guests to the earth and sky. We were given private, comfortable rooms with en-suites and full size canopy beds. I fell asleep to the comforting sound of a single cricket. In the morning, I awoke to a concert of bird songs.

In Kandy traffic was stopped for a street parade. We jumped out of the van to watch. It was Poya Day, a public holiday each month during the full moon that celebrates an event in Buddhist history. Young men and women in traditional costume swayed their hands as if drawing in the sky. Floats holding statues of Buddha followed.

Poya Day parade in Kandy, Sri Lanka.

My favorite Buddha statue was the one I saw at Gal Viharaya, a rock temple in Polonnaruwa. The layers of carved granite rock mimic movement. Buddha described individuals as “streams” rejecting the use of personal pronouns.

One of the four statues of Buddha at Gal Vihara.

The most visited historic site in Sri Lanka is Sigiriya. Visitors can climb to the ruins of a palace built atop a huge rock by King Kasyapa in the fifth century, no doubt to dissuade invaders. Sri Lanka has had its struggles with peace. Recurrent invasions from India and before that Portuguese, Dutch, and British colonialism threatened Sri Lanka’s three great civilizations at Sigiriya, Polonnaruwa, and Anuradhapura all designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites. One can travel throughout the country now without seeing much evidence of the brutal 25-year civil war (1983-2009) that ravaged parts of the country.

With lotus flowers in hand, we entered the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy. Inside, hundreds of people moved shoulder to shoulder solemnly laying the flowers on a long narrow table. We crossed a red carpet to the gold statue of a sitting Buddha. Ivory tusks stood guard. Drummers in traditional costume accompanied horn players. Because I had no other reference, I likened it to snake charmer music. We viewed intricate wall paintings and visited the library that held ancient texts. A monk was tying blessing bracelets on the wrists of visitors. My awkward approach to him resembled more of a genuflect than a bow.

Entrance to the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy.

I tried to flow with the stream of unfamiliar movements. I inched forward with hands in prayer position, opened the layers of petals in a lotus flower and laid it before a Buddha statue. When asked not to smell the flower because breath diminishes its purity, I obliged. I took my shoes off, climbed smooth worn stairs and crossed ground that resembled the sandy orange dirt of the runners’ lane in a baseball field. I wore white clothes which is the custom at sacred sites. Poured water and lit candles with a feeling of reverence towards something. But I was not sure to what. It was not to the artifacts. I started to recognize the people who crouched in prayer, chanted under umbrellas, and circled the circumference of buildings. They welcomed everyone, even me. It was dark outside when we left the Temple of the Tooth. The silver shine from a full moon and the warm glow of candles had transformed its daylight appearance into something mellow and magical.

Into the Jungle and Hill Country

We ventured inland to Sri Lanka’s forests and jungles. At a spice and herbal garden we followed the paths through tall foliage. Many Ayurvedic medicinal plants grow in Sri Lanka. “It’s nature’s therapy. Free of side effects,” said Dillipo, the Garden’s representative. We swallowed juices and tasted raw spices scraped from local trees – cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg, cocoa, pepper, and vanilla. I touched it, smelled it; let it linger in my mouth and savored a taste that had never been boxed.

Pathway at spice and herbal garden in Sri Lanka.

No designated overlooks or signs direct the traveler through the Hill country. Our van became a tiny white speck amidst the drama of the mountains and valleys rising and falling beside the two-lane winding road. It was as if the landscape had gotten a haircut. The land was well groomed, refined and beautiful. The lush tea bushes were being gently misted by clouds and at a distance pounded by waterfalls. In the hill town of Nuwara Eliya, the British influence was apparent. In its lake white swan boats floated. The golf courses and cricket fields stood ready for players. Horses whinnied. Colonial style houses perched on hillsides. The air temperature was pleasantly cool.

As someone who loves train travel, I relished the train ride from Nanu Oya to Hepathale through the Hill c ountry. My seatmate, a businessman named Kyma, told me the second-class reserve seats were best because you can enjoy the ride with open windows. He said First class has sealed windows with air conditioning and TVs, something of no benefit to him. America’s “safety first” attitude took a backseat as people dangled their limbs from the train’s windows and doorways. “Become an open window,” Bhante said. I inhaled the beauty of our view, hoping it would stay with me.

ountry. My seatmate, a businessman named Kyma, told me the second-class reserve seats were best because you can enjoy the ride with open windows. He said First class has sealed windows with air conditioning and TVs, something of no benefit to him. America’s “safety first” attitude took a backseat as people dangled their limbs from the train’s windows and doorways. “Become an open window,” Bhante said. I inhaled the beauty of our view, hoping it would stay with me.

Safari and Surf

The Buddhist way of do no harm applies to all sentient beings. The 26 wildlife national parks in Sri Lanka pay homage to the country’s animal kingdom. We entered Yala National Park in the Province of Uva to see animals of all kinds including spotted deer, water buffalo, leopards, peacocks, crocodiles, hundreds of bird species, and Asian elephants living freely. Our elephant sightings were limited. The only wild one I saw was a single male walking along the street outside the park. However, the Park’s savannah opened up to the shores of the Indian Ocean, which was an unexpected and delightful surprise.

Yala National Park

Part of the Community

Students and teachers at Hedunuwewa School.

Being with Bhante Sujatha, we were treated as honored guests by many generous people in Sri Lanka. But it was the children and teachers at the Hedunuwewa School and the doctors, nurses and new mothers in the maternity ward at the Peradeniya Teaching Hospital that truly warmed my heart. The school band played as the students in their white uniforms stood in rows to welcome us. They laughed and sang and were curious about us foreigners. “Will you sing us a song? Will you dance for us?” They asked. I played Hangman with the sixth graders. The principal at the rural, underprivileged school thanked us for bringing technology to their students. Our gift was a single projector.

At the hospital, we brought fruit baskets for the new mothers and an electronic monitor for the staff. Bhante’s teacher and two other monks joined us in a small room in the maternity ward. The staff set up the new monitor next to an infant incubator that had also been donated through Bhante’s Foundation. What looked to be a ball of kite string was unraveled and passed from each person inside the room. Nurses, mothers, monks and us travelers held onto the string as the monks chanted a blessing while the blue light on the monitor flickered. “Stuthi” thank you and a smile were the only ways to show our gratitude for the visit.

The Southern Coast

Stilt fisherman still tend their trade in Sri Lanka.

We visited historic sacred sites including Mihintale and the stupas in Jetavanaramaya and Ruwanweliseya, and moved on to the tsunami memorial, and an inlet where we watched stilt fisherman tend to their trade. Arriving in the southeast coastal city of Galle we shopped and explored the colonial architecture, stores, teahouses, and a fort that was built by the Portuguese to protect the port. Further along Sri Lanka’s southern coast we visited the town of Marissa where we enjoyed the beach and swimming in the warm, calmer side of the Indian Ocean.

On our last day, I was reminded of Bhante’s first Dhamma talk while we sat in the hotel rooftop cafe in Negombo. The sound from the ocean waves raised and ceased. Birds called to each other. A warm breeze massaged our bare feet. His talk was on “Acceptance of all things” including who we are on this day, at this time, in this place. The Dhamma talk was the only leadership role Bhante took during the 16-day trip. The travel experience was to be our own, not one narrated by him. The path he shared didn’t take us from one place to another, but to a deeper here.

A lovely recollection of a wonderful adventure.

An adventure it was. Thanks for reading.

Thank you for sharing your story. Sounds like a beautiful journey!