I should have a plan. The warnings keep coming. Transportation is not an issue. I work from home. But I still need to walk my dog. I have enough ingredients to make chicken soup and beef stew. Cereal, eggs, are shelved as usual. The temperature inside my house can be regulated with the push of a button. The upstairs always gets hot. Kitchen-level is comfortable and the basement, cool. It’s the opposite of how air outside works. And the air outside is changing.

The red berries on my holly bush have turned black. Ice encases all the tree branches. Squirrels hide in their dens. Plowed snow mounds tower above my head. January in Chicago is cold. The city averages seven days of below zero temperatures annually. Its coldest official temperature was -27 degrees on January 20th in 1985. I was young then and single. During the winter of 2013-14 there were 23 days recorded with subzero temperatures. I was married then, with a teenage son. Why was I fretting now?

National media headlines warn that the approaching mass of cold air will “blast,” “threaten,” “seize,” “attack” and “invade” us. Airplane flights and trains are cancelled. Businesses close. Schools close. My library closes. As does the bank. No mail is delivered. No garbage collected. However, the sky is blue. The sun is bright. Clouds match the color of snow. Local media refer to it as a cold snap. Here today and gone tomorrow. From a perch in my breakfast nook, the quiet stillness outside shifts from serene to eerie. No one is heating up a car or carrying a backpack to the bus stop. Mike and his dog Kramer are absent.

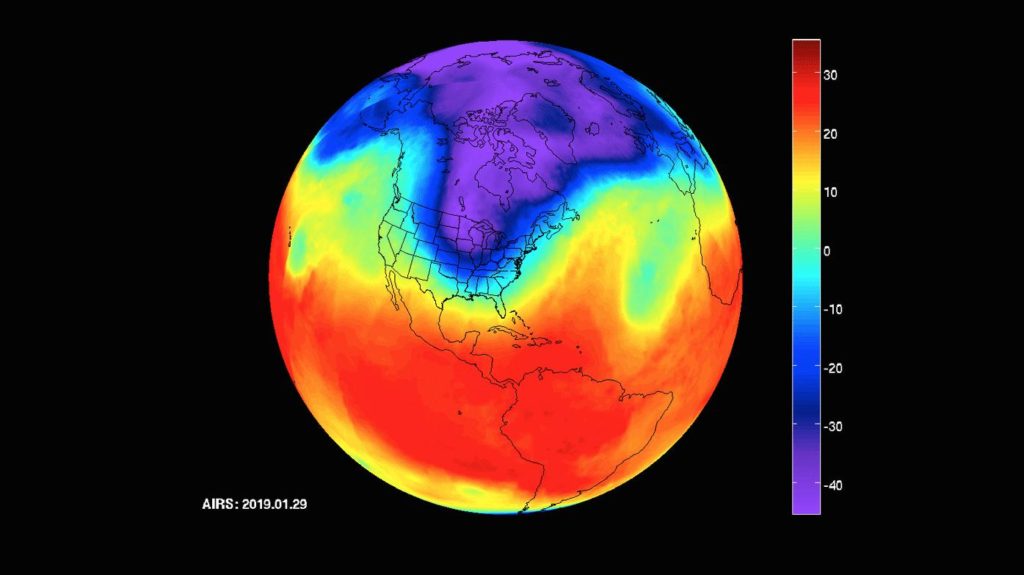

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech AIRS Project

For weather to become threatening, something has to prompt its emergence. With the exception of floods, the culprit is frequently wind. Invisible. Air starts moving when it interacts with different pressures. The bigger the difference in air pressure, the faster air flows. The jet stream, a thin band of rapidly moving air serves as a kind of boundary that usually keeps polar air well to the north of us and tropical air near the equator.

“The jet stream sets everything,” said Aditi Sheshadri, assistant professor at Stanford Earth. “Storms ride along it. They interact with it. If the jet stream shifts, the place where the storms are strongest will also shift.” The air stream is shifting, buckling like railroad tracks in extreme hot or cold.

I take a shower and steam coats the mirror. My hair dryer is a river of hot air. Taking a closer look, I see the swirling fan inside pushing the air.

When the jet stream brings warm air into the upper atmosphere it destabilizes the polar vortex, which is a constant swirling mass of frigid air usually centered around the north pole. It expands and weakens causing the jet stream to lose some of its strength too. The boundary line won’t hold. It drops toward the equator bringing pockets of polar air down with it. To the Midwest.

I change the filter on my furnace. I dress in layers. Warm socks. Silk tights under my pants. A wool sweater over an undershirt. Boots, a down-filled coat, hat when I go outside to walk my dog. The air is a butcher knife slicing my forehead and giving me an instant headache. My dog jerks up one leg and trots on the other three before I turn and go back inside.

No plan is needed when weather halts everyday life. I cook. I sleep. I read. And yearn for fresh air, outdoors. Community.